Peter Lopez

Transart Institue of Creative Research

Jean Marie Casbarian

22 February, 2019

The Responsibility of Working with the Black Body

“I wanted to be a man, and nothing but a man” –Frantz Fanon

At this year’s Grammy Awards, it was announced that Jennifer Lopez was scheduled to perform a medley of Motown hits in celebration of the historical Black record company’s 65th anniversary. Both before her performance and after, JLo emphasized that this music (Motown music) (black American music?) was what her mother loved. Motown music, she assured us all, was “passed down” to her and her siblings by her Motown-loving-mama.

Though she bookended her performance (which included a quick duet with Smokey Robinson, a brief piano interlude with Ne-Yo, a stripping down to a Vegas-worthy body suit, and a vigorous shaking of her money-maker) with assurances that this tribute was a reflection of her childhood connection to Motown, backstage she must have been made aware of the reaction to her number on social media platforms; “You can’t tell people what to love”, Lopez breathlessly announced, trying to keep up with social-media reactionaries. “You can’t tell people what they can and can’t do”.

The situation struck me as somewhat analogous to my practice of portrait painting. Particularly, my purposeful penchant for working (almost exclusively) with portraits of Black people.

When I began portrait work in 2009, like most artists, I harried friends, family, and co-workers to sit for me. A large proportion of the people who make up my social network happen to be either Black or Hispanic. Somewhere along the way of my studies, painting people of color (particularly African-Americans, Afro-Hispanics and Afro-Caribbean people) became less incidental and more political because of my discovery of the philosophy of Kerry James Marshall. Now, before Marshall, I had run across myriad articles, blogs, and interviews by artists, critics, and curators proclaiming the death of figuration. Marshall challenged this proclamation by highlighting the fact that galleries and museums are filled with centuries of white figuration. Marshall asked: how can one herald the death of figuration until there are just as many brown-skinned portraits in our art spaces as there are white-skinned portraits? And so, Marshall’s work, thematically, seeks to correct this inequality through the proliferation of hyper-Black figuration in his work. Marshall’s philosophy read as a rallying cry to me. He was right. And my body of work—with all the brown-skinned people I paint—could contribute, I believed, to Marshall’s sense of the need for equal representation in art spaces. As a result, I began exclusively painting portraits of Black and brown people.

But do I, a non-Black, non-brown artist have the right to take up the call for equal representation posed by a Black artist? Am I crossing the line as “ally” when I use the Black body for personal gain and personal expression even when it is under the banner of social justice? Does any white artist, in a time where Black oppression (votes), Black segregation (schools), Black socio-economic inequality (home ownership) still exist, have the right to use Black images and Black culture for an audience that is usually predominately white?

Finally, I wonder if the Black body in art automatically changes in terms of context when produced by non-Black artists?

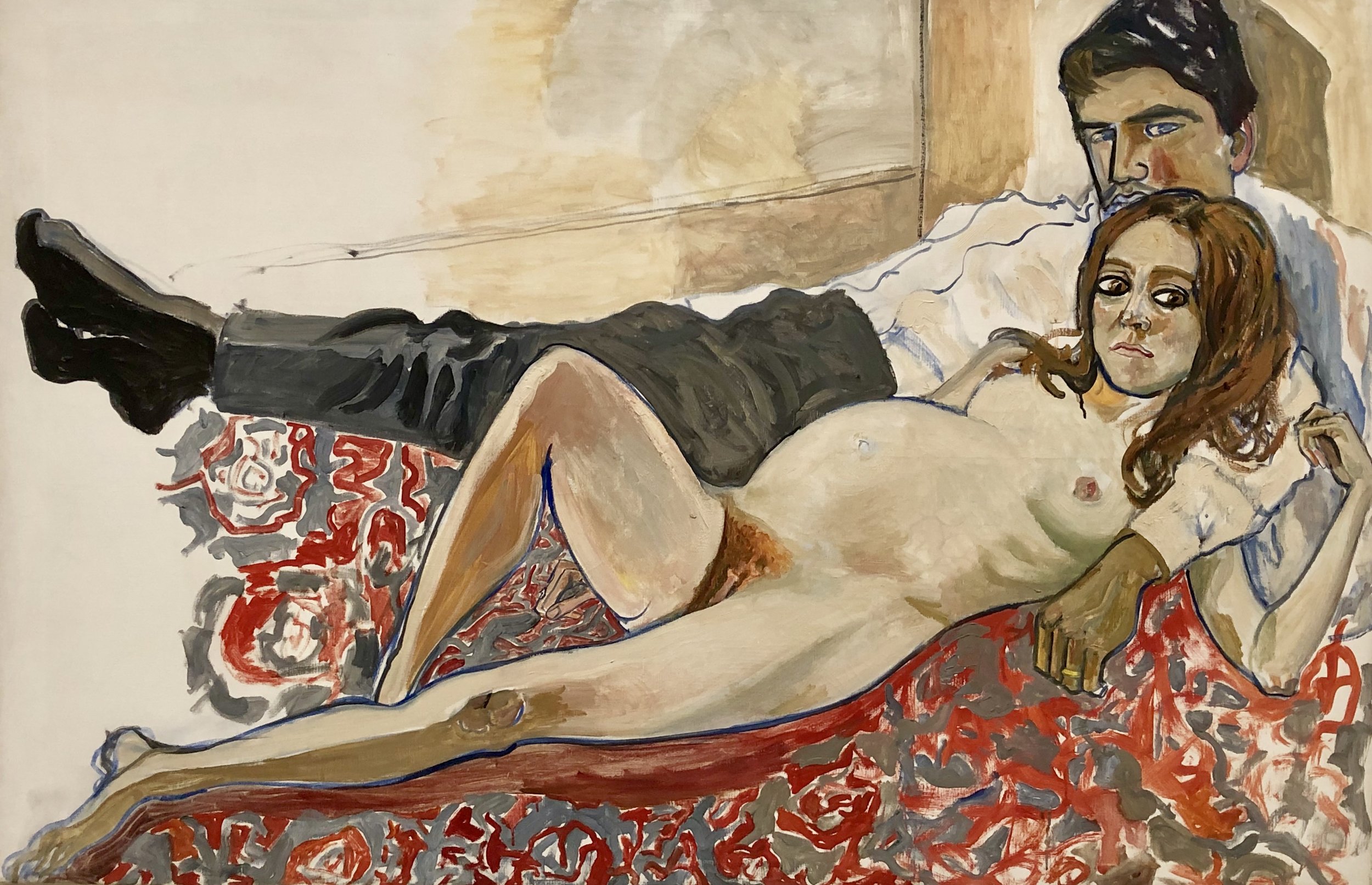

For some, the questions above are easily dismissed as making a mountain out of a molehill; After all, I am only painting portraits of Black and brown people. It’s harmless. But I submit the following scenario to consider: My portraits are hanging in a small gallery (largely consisting of Black men and Black women—some half-nude—some completely nude). The attending audience this afternoon is made up of patrons both white and Black. They stroll past the painting of the reclining Black male body on the couch, nude except for a pair of small, grey shorts. Someone takes a picture of the nude and pregnant portrait of a Black woman sitting on a floor. A remark is made about the flowers that decorate the young Black man’s chest in his portrait as he reclines on a brown bed spread and looks seductively at the viewer. A Black patron asks someone near him, “who is the artist?” and his gaze is directed to a corner of the gallery. There, standing in front of the portrait of a Black woman in dreadlocks sitting upright on a wine-colored couch, thick bracelets decorating her ankles, stands the artist: a tall man with dark hair and a white beard. He looks white, He is definitely not Black. “He sure likes to paint Black people”, the man says to himself before approaching the artist. The Black patron, waiting a moment to talk to the artist, does not recognize the artist per se. He doesn’t know him. But being a Black man in America, he recognizes the artist by phenotype. Unlike the Black patron and the artist’s preferred subjects, the artist’s skin is pinkish, with blue running through the veins in his hands. The artist’s head is covered in waves of straight hair that is easily managed. The artist’s nose is straight and his lips are pink. The artist can pass in and out of places unmolested. The artist can drive across the country undisturbed. The artist is welcomed into rooms of all types with smiles. With age, the artist has collected many rights that go unchallenged (including the right to paint whomever he chooses). So, the patron must know—and asks—“why do you like to paint so many Black people?”

As the artist, I could simply answer that Black people are the people who I am always around. I could inform the Black patron of my credentials by citing that I grew up in Lefrak City and currently teach in Harlem. I could explain to the Black patron that anyone concerned with my being a white man painting Black people should not worry because that is not what is really happening here: I’m half-Mexican. I could reveal to the Black patron that I love working with brown skin and the palette that brown-skinned people allow me to use. Finally, becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the question and the dubious look on the Black patron’s face accompanying each answer, I would submit that I am fighting for equal representation in art spaces for people like him. I could end with, “listen, I just love painting Black people. And you can’t tell people what to love. You can’t tell people what they can and can’t do”.

Yet in 1991, Glen Ligon seemingly did just that. Ligon displayed an installation titled, Notes in the Margins of the Black Book, at the Guggenheim. The piece included pages from Robert Mapplethorpe’s, Black Book, (where the photographer mostly displayed the male Black form through a lens of homo-eroticism) alongside quotes from a variety of people that were paired with each image as a type of reaction to the image (and Mapplethorpe’s project as a whole). Through his selection of quotes, Ligon (a Black male artist) was not attempting to tell Mapplethorpe what to love or what Mapplethorpe can and cannot do. Ligon’s mission was to alert Mapplethorpe that, to a Black man, these images were problematic. How so? The problem with the problem is that it cannot be explained in simple terms such as “racism” or “othering” or “objectifying” because such terms are often taboo in the bohemian, free-expression world of art and artists; they are censoring.

I imagine that Ligon, in curating these quotes, had to carefully vet each one to be sure that the quote did not oversimplify the problem he found with Mapplethorpe’s Black Book. Probably the quote that best exemplifies the problem Mapplethorpe’s work created was a quote Ligon chose by James Baldwin: “Color is not a human or personal reality; it is a political reality.”

While the concept of color-as-political-reality transcends what appears in an art space, it is important, for the sake of this exploration, to hold the idea under that lens when it comes to art spaces and the art world at large. The Guggenheim’s mission statement claims that its foundation engages “both local and global audiences”. On its website, the Whitney proclaims itself to be the “preeminent institution devoted to the art of the United States”. The problem that the Guggenheim, the Whitney, and any American art space runs into is that both its “local audience” and/or the work of the American artists it “devotes” itself to is inherently racist and operates within a racist society.

Though oftentimes not very convincingly, the art world has pillared itself as a space that rises above the muck and mire of racism, genderism, sexism and most other –isms. But the art world lives in the real world. And the American art world lives in America. And one cannot be divorced from the other. “Once and for all”, Frantz Fanon wrote in Black Skin, White Masks, “we [must] affirm that a society is racist or not”. He goes on to affirm that for one to say that a society is “only partly racist”, only racist in “some geographical locales”, or that racism only exists in “certain subgroups” in a society is “characteristic of people incapable of thinking properly”(66). In short, when dealing with the political reality of color in the United States of America—in any sphere within this country—“there is no place called innocence” (Yancy 233). What is being presented here is an idea that must be fully considered before moving forward: If the United States of America is a racist country (specifically white people against the existence and/or freedoms of Black people), then all citizens of the United States of America are racist (specifically all white Americans in some form or another and to varying degrees).

This declaration, of course, calls for immediate protest (specifically from white people): “But I’m not racist!” “My family didn’t own slaves!” “My cousin is Black!” “I’m married to Black woman!” In his book on white fragility, Robin Diangelo fleshes out these knee jerk reactions when white people are confronted with the racism that they have been acclimated into (through family, living conditions, and media) by citing the fact that because white people so “seldom experience racial discomfort in a society [they] dominate, [they] have [no] racial stamina”(2) to clearly think this through to its logical conclusion: If we grow up in a segregated society where 93 percent of the people who “decide which TV shows we see are white”; 85 percent of the people who “decide which news is covered are white”; 82 percent of our “teachers are white”, then we must live in a society whose information is being directed by white people (including how whites translate the non-white) (31). To put a finer point on things without beating a dead horse, I’ll use a Fanon line and embed within it an analogy that I hope clarifies the above as it may read as a hyperbolic statement; Fanon writes that “it is utopian to try to differentiate one kind of inhuman behavior [a white man displaying Black bodies on an auction block for a predominately white audience’s viewing pleasure and possible procurement in Mississippi in 1826] from another kind of inhuman behavior [a white man displaying Black bodies in an art space for a predominately white audience’s viewing pleasure and possible procurement in New York City in 2019]” (67). Further, I would argue that any attempt to distinguish my work with Black bodies from the work of Mapplethorpe or the work of the slave auctioneer is an example of white privilege.

It is worth a moment to briefly pause here and address my affiliation with whiteness and possible/probable designation to some as a white artist. Ethnically I am half-Mexican and half-German. My last name is Lopez. Phenotypically, depending on the room, I am white, some type of Latino, Greek, or Middle Eastern. Like most mixed race people who know its cooler to be mixed than to be white, I have always leaned heavily on my last name (despite not speaking Spanish fluently or knowing that side of my family). And on questionnaires, I always bubble in “Latino/Hispanic”. This, however, does not allow me to escape my phenotypic privilege.

On the site, hyperallergic, Ron Wong created a tongue-in-cheek syllabus for “making work about race as a white artist in America”. His syllabus’ research project for “week three” requires students to explore the question: “when did you discover you were white?” Wong challenges the white artist who wants to make work about race to first understand their whiteness, locate the “defining experience” of when you came to understand that you are white and all the privileges that you inherited with that designation, and then “figure out how to speak to this defining experience in your work”.

I found out that I was white (could be perceived as white, had a foot in whiteness) when one of my models (Gilles, the man from Guadalupe with the long dreds) during a conversation about white teachers in predominantly Black schools, said to me, “Peter, you know you’re white, right?” I discovered I was white when Jasmine, my girlfriend and often-reluctant-model and I were walking through Harlem and a young black man walking perpendicular to us stopped and let us pass and Jasmine said to me, “you know he just white-maned you, right?” I realized I was white when I was speaking to Dionne, while painting her portrait, about my open and often vitriolic disagreements with my principal (whom she knew to be Black) and Dionne suggested that I was so verbally open to expressing my disagreement with my superior in such a forceful manner because he was a Black man and not another white man. In short, I discovered I was white when three Black figures in my life felt they needed to tell me that I was white. The need came, I believe, from their perception of the danger that my unrecognized whiteness presented to my character: “non-raced white bodies”, Yancy notes, “are able to ‘soar free’ of the messy world of racism” (45). Diangelo identifies this danger as what ails the white progressive who, “thinking he is not racist or is less racist, or ‘already gets it’” puts all their “energy into making sure that others see [them] as having arrived”(5). The above mentioned Black figures in my life saw me soaring (saw me believing I had arrived) and decided they needed to guide me down. They understood that and recognized that my penchant for tackling the question of race (in conversation about society, education, social justice, or the art world) was a usurpation of those themes because in my very determinate remarks—“museums and galleries are racist spaces because they lack Black figuration”—I was taking it upon myself, with my phenotypically white existence and experience in this country, to define what is and isn’t racist. Is this not the very apex of white privilege?

It is.

And it is this apex of white privilege/white power—“defining what is and is not a racist act” (Yancy 50)—that Aruna D’Souza discusses as practiced in the art world in her book, Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts. In the book, D’Souza cites three separate incidents where art institutions not only overlooked blatantly racist acts by white artists in their use of Black culture, but defended the white artist’s decisions under the banner of artistic freedom. Specifically, DŚouzaś book exposes and explains three instances where the white-controlled world of art spaces have transgressed against the collective racial sensitivity of the Black community regarding the use of Black tragedy (with Dana Shutzś Open Casket), the use of the N-word (for a drawing exhibit by white artist, Donald Newman, titled The Nigger Drawings), and the erasure of the Black voice in an exhibit titled, Harlem On My Mind which did not feature the work of any Black artists. The book’s intention is to expose, not only the art world as primarily a space for white artists and the white art world with an occasional bone thrown at marginalized communities, but the shocking depth of insensitivity on the part of curators, art critics, and museum officials when white artists use Black culture, Black references, Black history for the benefit of shock or self-promotion.

In D’Souza’s discussion of the reaction stirred by the Whitney’s showing of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket in its 2017 Biennial, the author writes: “The question of when, and on what terms, a person is justified in taking up the cultural forms and historical legacies of races to which they themselves are not a part is always fraught, but especially so in the art world where cultural ‘borrowings’ are the cornerstone of the European avant-garde tradition we’ve been taught to admire” (37). Where is the line, for the non-Black artist, between making art that concerns the Black subject or Black culture, and cultural appropriation? If the purpose for Mapplethorpe in his Black Book was to call attention to the beauty of the male Black form, the question becomes: is it his place, as a white man, to prostheltize over and profit from the beauty of the Black body? If Dana Shutz’s goal with making Open Casket was to promote the tragedy of Emmitt Till’s murder through the lens of a fellow-mother, as she claimed, the question becomes (became): is it her place, as a white woman, to shift the lens of the image away from the lens of white-racist violence? The question for me becomes, if my goal is to aid in the proliferation of Black figuration on the walls of galleries and museums, as Marshall suggests is needed, is it my place to take up that cause? (Or was the unsaid continuation of Marshall’s philosophy that more Black fifuration needs space on gallery walls made by Black artists?)

One may attempt to begin an investigation into this by asking me, what is it that you do with the Black body in your work? The initial answer is innocent enough: portraiture—a capturing of a likeness and sometimes a mood, sometimes a moment, sometimes a relationship between myself and the sitter. Yet the science and philosophy around looking at a human subject suggests that looking is never truly innocent.

In The Hidden Dimension, anthropologist, Edward T Hall, cites artist, Maurice Grosser’s observation that the portrait differs from other types of painting because of the “psychological nearness” between sitter and artist. That distance, according to Grosser is usually between four to eight feet. “Nearer than three feet, within touching distance”, Grosser reports, “the soul is far too much in evidence for any sort of disinterested observation [emphasis author’s]” (78). At portrait distance, Grosser suggests, there is something else occurring in the mind of the artist than a mere capturing of a likeness, mood, or relationship. We can adopt ideas from James Elkins, The Object Stares Back, to flesh out what Grosser may be suggesting is behind this interested observation: “Looking is not merely taking in light, color, shapes, textures, and it is not simply a way of navigating the world. Looking is like hunting. Looking is like loving. Looking is an act of violence and denigration. Looking immediately activates desire, possession, violence, displeasure, pain, force, ambition, power, obligation, gratitude, longing” (28).

When the above discussion of looking is overlaid atop the context of the white portrait artist looking at the Black body, the idea of just looking (just making a portrait) itself becomes problematic. This problem is explained more fully by Yancy who explains that the Black body (historically as on the auction block and contemporarily as in an elevator) is under continuous and tremendous “existential duress” when prey to the white gaze. Under the white gaze, Yancy explains, the Black body is both hyper-violent and hyper-sexual. Yancy provides a number of points throughout Black Bodies, White Gazes that it may be more purposeful to the cause of this exploration to record them as a series of questions posed to the non-Black artist working with the Black body:

When looking at and working with the Black body:

1. Is the non-Black artist “confiscating” (taking or seizing someone else’s possession with authority) the Black body from the Black subject? (Yancy 2)

2. Is the non-Black artist “[re]constituting” and “[re]configuring” the Black body? (Yancy 3)

3. Is the non-Black artist “flattening” the Black body by “eviscerating” the Black body of “individuality”? (Yancy 4)

4. Is the non-Black artist “reducing” the Black body to a state of “non-being” by displaying that Black body to a predominately white audience which practices this reduction of the Black body “systematically” on a regular basis outside the gallery walls? (Yancy 7)

These questions are too complex to go through here and even if I wanted to complete the exercise there is no guarantee that my answers can be honest and pure and not distilled through the sieve of my desire to be the very best ally I can be; the same way that I could not trust my own assessment of my whiteness (within the sphere of the Black/white world) and had to rely, at least fractionally, upon Black people to locate me, so to, I believe must the above questions about my work as a non-Black artist be at least fractionally answered by the Black reviewer.

For along with the danger of working with the Black body because of the white-eye-filter that the Black body has to go through without the intentional consultation of a Black audience (detractors may see this as an asking-for-permission) in 21st century America, there is also the danger of erasure.

In an article in the New York Times, writer Paul Sehgal defines erasure as “the practice of collective indifference that renders certain people and groups invisible”. I am tempted to go even further and suggest that any non-Black artist who takes up a Black artist’s call to inject more Black and brown figures into galleries and museums is in danger of erasing Black artists: of taking up space, if you will, in the realm of Black figuration that should rightfully belong to the myriad Black artists that are working now.

Looking at social-media reaction to JLo’s Motown tribute, I spotted one woman’s reaction as stating that what JLo was engaged in was erasure; the tribute could have and should have been performed by the myriad Black artists working today. The woman suggested that what JLo was doing was normalizing the displacement or replacement of a Black performer for an obviously Black tribute to an entity that was a large part of Black music history. Her suggestion had me imagining that in five more years we may see a Motown tribute by Taylor Swift (with less of an outcry), and then Justin Timberlake (with even less of an uproar), and then Miley Cyrus (with little to no mention) because these Motown tributes have become uniformly non-Black. I can even imagine that the producers of these tributes manufacture a reason for these non-Black performances as a way for white performers to recognize Black excellence. Horrifying.

The point is that in 21st century America (where we see the poison of racism as getting more potent by the decade) we can no longer sit on our hands while people do what they “love” without questioning the potential harm of that love simply because they believe that that is their right. Had Mapplethorpe addressed the potential problem of his Black Book before Ligon did, his work would have taken on a different meaning and, I argue, taken on some sense of responsibility. Had Dana Schutz accompanied her Open Casket with an essay investigating the problem of a white woman (who was the instrument of death for young Mr. Till) painting that painting, she could have started a very rich and very much needed conversation about race, appropriation, responsibility, and art. Neither artist seemed to “love” the idea of discussing race as they did in using it.

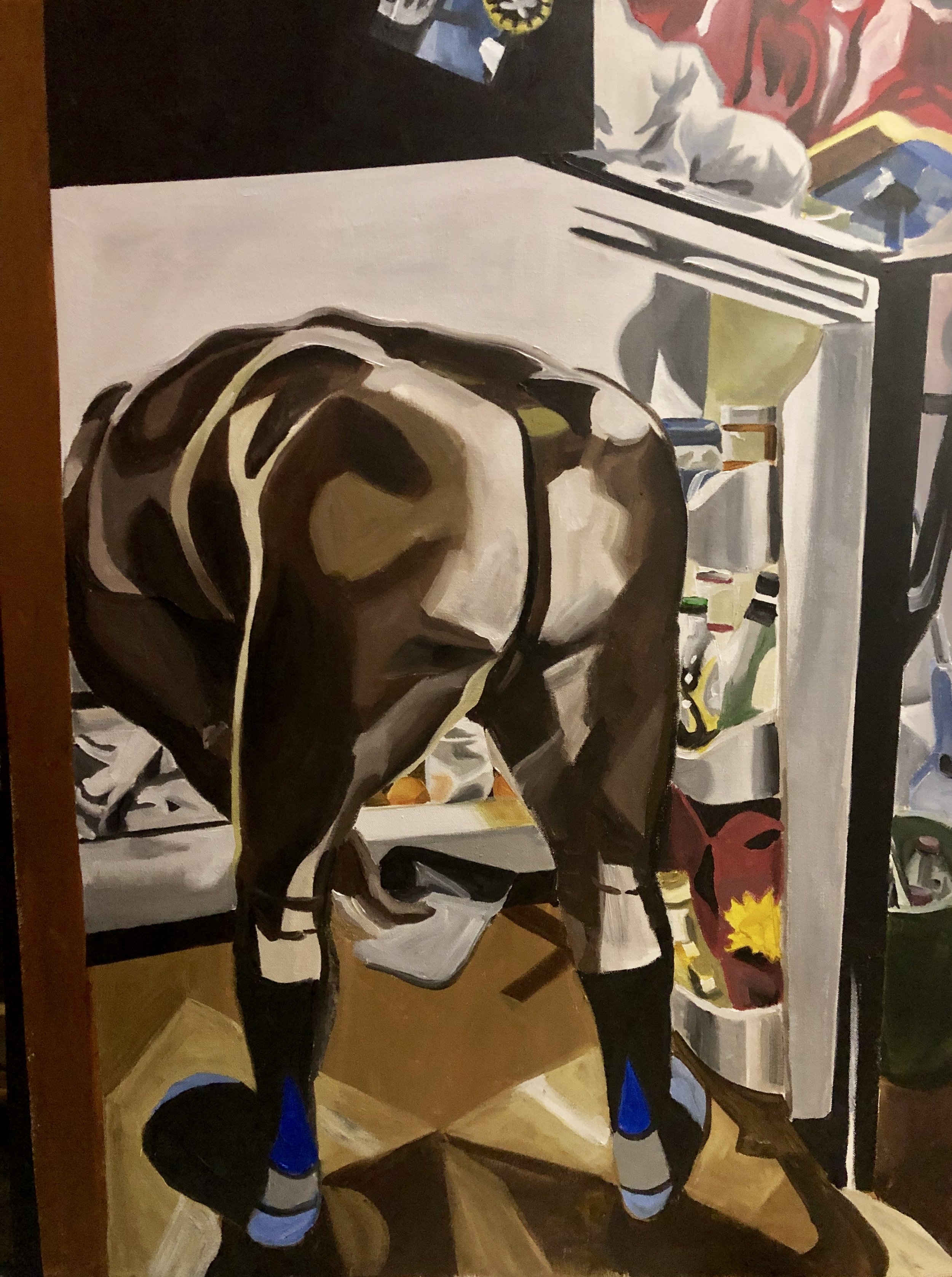

In the 1970’s, Alice Neel, a white artist residing in Spanish Harlem painted her friends, family, and neighbors—some of whom were Black and brown people. And, in spite of the message of this entire essay, Neel’s work was largely unproblematic. In a write-up about Neel for The New Yorker, Hilton Als explains why: Neel, according to Als, “didn’t hide from the erotics of looking”. “You can tell”, he continues, “when she was turned on by her East Harlem subjects—by their physicality, mind, and interiority”. But, he argues, there was something about Neel’s work that spoke to a “collaboration, a pouring of energy from both sides—the sitter’s and the artist’s”. Neel’s handling of people of color shows us the “humanness embedded in subjects that people might classify as ‘different’” largely because “she did not treat colored people as an ideological cause but as a point of interest in the life she was leading there, in East Harlem” (Als 6).

I plan to continue to paint Black and brown people but I also plan to drop the philosophy I attempted to adopt from Mr. Kerry James Marshall. I can only hope (but cannot insist) that when people view the full oeuvre of my work and note to themselves, “he sure likes to paint Black people”, that they will see in my work what Hilton saw in Neel’s—an “inclusive humanity”. And if they do not, if the work still feels problematic, I can, at least, report that that is understood, that I have attempted to investigate this, and that I hear it and that I take responsibility.