Feature in OUT magazine

Beyond Gender Exhibition with guest Andre de Shields

Interview by journalist Lia Chang at the Beyond Gender exhibition opening: June 22, 2023

Oz

In the same month that I began my journey towards accepting that I am an artist, I fell in love with someone. It was May of 2018 and only three weeks before I was heading off to Berlin to start an MFA low residency program when I met Chris. I was elated to have found someone after many years of not interacting much in the dating world. So instead of hanging out in Berlin after art workshops, I would rush to the apartment I was renting to talk to Chris on my laptop. When I got home from Berlin I went straight to his place in Brooklyn.

I painted him three times and I wrote about being in love and being an artist; I was so consumed by him that my first post on my mandatory blog (necessary for the MFA program) was about Chris with an accompanying portrait I had done of him and a written portion on how art reflects life and how he was my life and so now he was my art. I imagined then, I think, that I would paint no one but him.

Three years and a pandemic later things have changed. The shine is off the relationship. We have fought over and over, much of the fighting being about my work: my painting.

I realize now that I was not being handed love and art at the same time but actually two competing forces at the same time.

I moved in with Chris and he complained chronically about the smell of the turpentine and cried about my having a drag entertainer sitting for me. He got drunk and confrontational when he found out I painted a porn star and met me with passive aggressive silence when I would come home from a residency field trip. He admitted to not liking the idea that I have studio space separate from the apartment we now share and told me that my sitting sessions (accompanied by wine and snacks and conversation) were akin to first dates.

In 2017, a Turkish photojournalist named Burhan Ozbiliki covering a gallery opening witnessed (at the opening) the assassination of Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov. The picture he took has since won a prestigious art award and was written about in Vulture by renown art critic,Jerry Saltz.

Ozbilici took this photograph not from a crouching or hiding position. But standing straight and facing and focusing on the action. One may wonder that he didn’t understand that he was risking his life for an image. People don’t know how much the Artist will risk for an image that, whether real or imagined, is once-in-a-lifetime and a thing that only the artist—at risk of life, limb, family, marriage—can author: how much it IS worth it ALL. What struck me in looking at this photo and understanding the real potentially fatal danger Ozbilici put himself in to get this shot 5 years later and 4 years into a relationship that is hobbling on its last legs is that I know what Oz knows: the art is what matters: not death or family or leaving children without a father: and certainly art matters more than a 4 year relationship.

Chris has been fighting a losing battle. The art will always win. I will follow it until I, myself, am on my last legs.

SPRINGBREAK 2022

It was amazing to take part in this year’s SPRINGBREAK art fair. Thanks to Andrea Bell for curating and Jason Lowrie for producing music to accompany my pieces. The theme was Naked Lunch and it was an honor to exhibit beside such talented artists who worked so hard at turning two floors of Manhattan office space into a explosion of painting, photos, sculpture and wild landscapes that poured out of the offices and into the souls of all who attended.

Back to Basics(?)

I recently went to a small gallery in the Meat Packing District and was met by the gallery’s director at the door. She was a warm and lovely woman who I could tell in our lengthy conversation lived a sensational life. As she began showing me the works, she became quickly apologetic; “we usually have here”, she informed me, “more Avant garde art than this”. “This” was painting, figurative painting to be exact. Before she could go further I told her I was a figurative painter. We neatly rolled away from the subject and talked of life which was how I came to understand she lived a rich and full one.

While I felt the familiar sting of “irrelevance” hearing someone important (and to me she was important) speak about figurative painting, I could not help but recognize that a portion of me agrees with that assessment: figurative painting is done.

And yet the conundrum is: figurative painting is what I do. Specifically portrait painting.

Recently, I have explored other ways to work figuratively by taking a thematic approach looking at archives, trauma, memory, and bi-raciality (that’s not a word yet?). I have also explored the materiality of the canvas by pulling my work off the stretchers and hanging them like tapestries.

But then, the call came.

My partner’s son, Chris Jr. came to visit. We had met before but had not spent significant, quality time together. Well, I thought, what better way than to have him sit for a portrait? I imagine this is how drug addicts reconcile feeding their addiction: finding some disconnected excuse to once again pick up the needle. For me, that needle was a brush.

Chris Jr. obliged me for over three hours and, as usual, he and I were thick as thieves by the end of the session. Surprisingly, I had liked what I had done. I had achieved something, I felt. The work was good.

Back in 2018 when I started my MFA at Transart, we MFA candidates had an opening critique of our work. Most of the panel were polite and supportive. But Kim Schoen was the Simon Cowell to everyone else’s Paula Abdul’s. “You should only ever do portraits” she told me. “Nothing else”.

She was, to me, also important.

Residency Unlimited

I have just finished a residency here in Brooklyn called Residency Unlimited run by the incomparable Nathalie Angles. This past weekend the end-of-residency exhibition was put on at 360 Court Street and it was amazing to see all the people come out to join us. People are starving for art and RU was there to serve. The show was titled “Sublime Encounters and Other Worlds” and was curated by Andrea Bell. Below is a link to watch Andrea interview all five of the artists-in-residence including me!

Reading Diary: Utopia Amiss (Sattar Hasan)

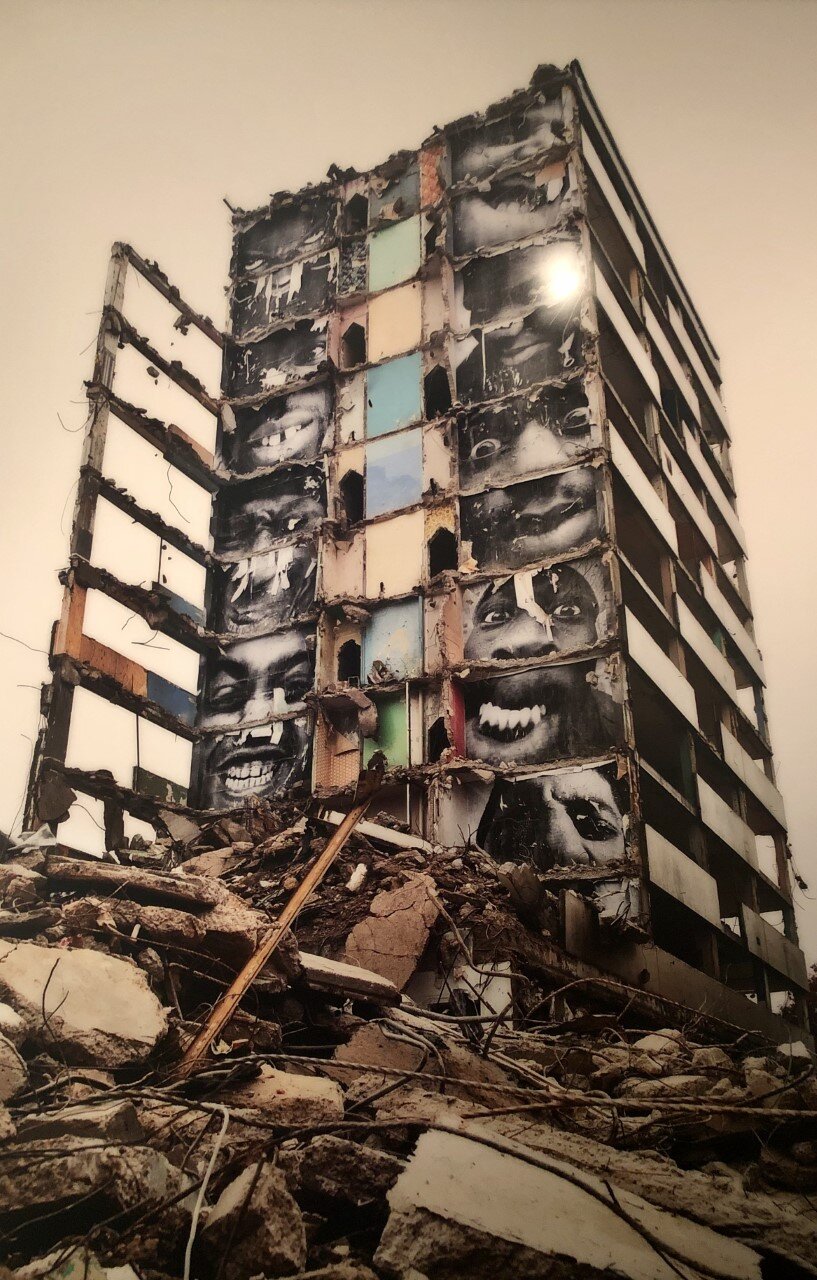

Interestingly enough (in connection to the readings in Black Utopia”) I am currently working on a series of paintings that are inspired by thoughts of Black freedom, Black utopia, and Afro-futurism. Unlike the premise of Zamalin’s conclusion however, the images I am working on do link Black utopia to violence: to violent revolution. It is difficult for me to imagine a Black utopia absent a scorched earth event. In this way, I find a lot of “sense” in Sun-Ra’s “philosophy” as stated in the book that this “cruel planet”, this “mean world” looks to never afford Black people the possibility of utopia or anything close to it.

Reading Diary: Unambitous Stripper (Lewis)

Parts of pages 213-219 of Roslyn Bologh’s Love or Greatness remind me, strangely, of one of the main theses in the book, The Greeks and Greek Love by James Davidson. I’m not sure that these are opposing ideas, similar ideas, or ideas that can play with each other.

For Bologh, in the midst of erotic love, “the recognition that while the self is appearing to be a subject, s/he can also be an object makes for the playfulness of social interactions”. A key feature to this playfulness, according to Bologh, is “suspension of commitment” to ones role as either position (object or subject) (desired or desiree). These ideas are labeled as a feminist mode of erotic love and it reads as such: erotic love is the fluidity (and balance) to be both the object of interest and the interested party.

In his book, Davidson explores the prevalence and seeming acceptance of male homosexuality in Ancient Greek society and posits that much of this “acceptance” was predicated on the pursuit of homosexual sex but not on the actual act of homosexual sex. That is…one can chase and one can be chased, but one must never catch or be caught.

There are, according to Davidson, strictly prescribed roles for sociable, socially acceptable male homosexual behavior. Specifically, these roles consist of the “eromenous” (the youthful, smooth, young male) who is pursued by the “erastes”—the older man doing the pursuing. The strictness in age of the roles and the concept of the chase are important to the acceptance of this sociable behavior; the older erastes is expected to make an object of the eromenous. However, according to David, the eromenous is expected to flee from his role as object. In other words, Davidson posits that in many places in Ancient Greek society, it is acceptable for a man to lust after a younger boy and it is acceptable for a younger boy to be lusted after by an older man; it is acceptable for the older man to pursue the younger man (say, attempting to give the young man a gift) but it is not acceptable for the young man to be “caught” (accepting the gift/ acknowledging the pursuit).

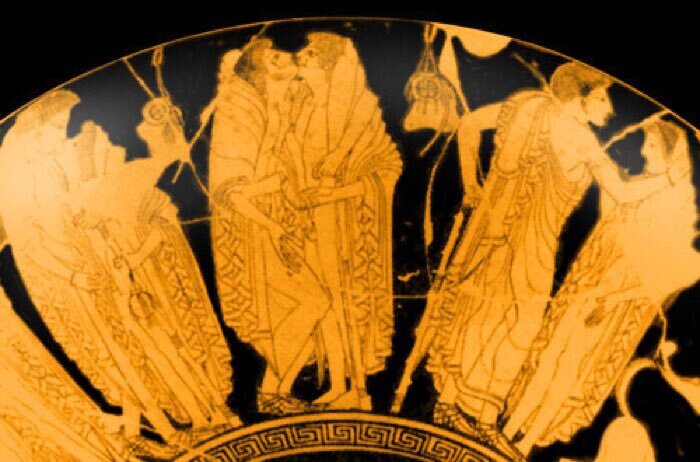

Davidson uses many Greek myths and Greek pottery art to illustrate his complex concepts of “Greek love”.

To illustrate the above concept (I’m not sure if it’s symmetrical or asymmetrical), Davidson refers to the Peithinos Cup. This cup is decorated with repeating images of an erastes very close to an eromenous. In each couple’s background, there is a bottle of oil (the setting is assumed to be a gymnasium). As the couples vary in postures, the oil bottle in the background varies in its position; for the couple who is depicted as the furthest apart, the oil bottle is upright (Davidson reads this as a symbol of “social acceptability”); for the couple that are illustrated as the most sexually engaged, the oil bottle is tipped and spilling over (read as “socially unacceptable”).

Bologh’s writing emphasizes fluidity in erotic love: the ability to switch roles between desired and the one desiring (in both homo and heterosexual relations). Davidson emphasizes strict rules and roles in the erotic homosexual behavior of men in Ancient Greece yet a key feature here is also non commitment to the act: it is also play. And in a sense, there is also fluidity: an eromenous has the capacity (the destiny?) to age into becoming the erastes.

Reading Diary: The Transcontinental Neighborhood (Bowdidge)

In Chapter 5 of Translocal Geographies (“London: Belonging and ‘Otherness’ among Polish Migrants after 2004”) Ayona Datta discusses how Polish migrants attempt to settle into London-as-home mostly through “produc[ing] and reproduc[ing] social forms that belong to particular nation states” and moving from place to place in order to work; these moves have the migrants primarily skirting around the London they believed they would be living in and living in neighborhoods that constitute the “other” London, the ethnic London, the poor London, the less opulent London—the London that does not represent the West (Shakespeare, The Beatles) that these migrants imagined.

The chapter makes me think about the state of African Americans—particularly in NYC.

As a teacher in Harlem New York, I have several times taken my African American students to museums and Broadway shows. “Why are we the only Black people here” has been a common question on these outings. Though these students were born and raised in New York City, these trips to midtown and downtown Manhattan (Union Square, 5th Avenue, Broadway) were, for many of them, the first time that they were seeing the “other” NYC.

Though my African American students are not migrants, one can argue that they seem to have formed (or have been born into) a type of “ethnoscapes” that Datta describes. Many of my students are trapped in the ethnoscape of Harlem (of Blackness) they live there, they go to school there, they work there.

New York City has a history of purposefully segregating neighborhoods. Redlining, gentrification, white flight, all play a part in ensuring that Black people live among Black people—and away from white people. Compounding this, America has a history of economically marginalizing Black Americans. One can argue given these two facts that white Americans have historically treated Black Americans as though they are migrants in their own country: unable and unallowed to participate in the America advertised in mass media, in televison programs, on Broadway.

Like the Polish migrants in Datta’s chapter, Black Americans have had to invent their way in and around the America that is denied them: the America of equality and prosperity and opportunity. But unlike the Polish migrants , the concept of an ethnoscape for Black Americans comes in the form of a separate-American-culture—or black nationalism.

Wahneema Lubiano states that “black nationalists have detailed for black Americans an origin and a destiny outside the myth of ‘America’. One can read Lubiano’s use of the term “cultural imperialism” as a substitute or alteration to Datta’s term “ethnoscape” when it comes to Black Americans. “Lacking a homeland and a sovereignty”, Lubiano continues, “culture is all we can ‘own’”. Black Americans have, in short, created an “other” American culture and an “other” America while, at the same time, attempting to infiltrate the white America (its economic institutions, its educational institutions, its political institutions including its presidency) that is theirs by right of birth, history, and the very constitution that shapes white America.

Recently, however, a revolution has gripped the nation as a whole and it seems infiltration is no longer working at a satisfactory pace. As Black America has done in the 60’s, Black America is once again beginning to make demands on white America; these demands fall into the realm of Datta’s view of how the Polish migrants in London had to live in the “other”, ethnic London (a territorial concept) in that Black Americans are usurping what has been assumed (and practiced) as de facto whites-only spaces.

Two of the most outstanding examples of this usurpation are Broadway’s “Black Out” where Broadway shows are reserved for Black-only audiences and the BLACK LIVES MATTER street mural freshly painted on 5th Avenue in front of a building owned by white America’s current president.

"Agnes Dennes" by Jeffrey Kastner

Of all Agnes Dennes’ works discussed in Jeffrey Kastner’s writing the work that touched me the most was Human Dust. I was fascinated at the idea of the creation of a life and all its minutiae and picadillos. It reminds me of a novel written by JM Coetze which was a fictional memoir of his own life. In the novel (about himself after his passing), the author discusses himself through close relatives and ex lovers.

It is an interesting experiment of measuring one’s own life through the eyes of others. We create and recreate our personal narratives in our minds and many artists do so publicly. But what is the record of our lives written by those most intimate with us?

I believe myself to be humble. My mother thinks I am arrogant.

Chris believes himself to be a thoughtful, self-sacrificing partner. I think he is rather selfish.

My friend, Barbra, believes that she has her fingers on the pulse of progressive politics. I think she practices the politics of an old lady still enthralled with JFK’s good looks.

I wonder if Dennes’ concept can be transformed (has it been?) into some form of art therapy that serves to deepen our understanding of how we are perceived outside of ourselves and the potential impact of who we are on others.

My mother told me she thought I was arrogant over two decades ago. It was a random comment apropos of nothing and not discussed further. But it has haunted me ever since. It sits in front of everything I say and do. Many times, I push it aside and move forward. But I do not try to eradicate it from my mind.

I think it is important.

"What Should An Artist Save?" -Thessaly La Force

“On a larger scale, the drive to chronicle is something that possesses us all” —Thessaly La Force

The Archives of my Partner, Chris Joseph

Death is running theme in many of Chris’ archives. The three matriarchs of his life (pictured in the frame) died back to back when he was on his mid-20’s. He buried them all single-handedly. Later in his life, he died for three seconds in a hospital from pneumonia. On this mantle, Chris piles up the records of funerals: not just of the matriarchs, but all subsequent funerals he attends: no matter how distant the relation.

One of several collections of letters, bills, and catalogues.

A box full of Chris’ son’s toys. Chris Jr. is now 30 years old and lives in Florida. There are three garbage bags in our hallway full of Chris Jr’s clothing (children’s clothing). My studio was Chris Jr’s bedroom. His son’s bed frame is still standing against a wall in there.

An old TV guide, a newspaper touting the benefits of garlic and vinegar (two things you will always find in our home) a copy of the Penthouse magazine featuring Vanessa Williams that got Williams dethroned as the first Black Ms. America. Chris froths at the mouth if any program comes on that covers Monroe’s death.

Programming textbooks from two decades ago.

Glassware from various events that Chris has attended. and dried roses that are important to him (Im’ not jealous). If you look closely, there is a broken glass in a glass. He will not throw it away.

VHS cassettes in the era of digital download. Chris also has a VHS player hooked up to the television and another VHS player laying around the apartment as back up.

An old computer monitor not in use but not going anywhere anytime soon. She lives behind the couch.

An old phone that is not plugged in or in working order. There is another that lives behind the television that is plugged in but muted and not in use. I do not know why he keeps it connected. One can hear the ghost of a ring every once in a while of someone calling. Perhaps it is a wrong number. He never picks it up,

Three boxes of chocolates that have been sitting on the TV stand for many years, unwrapped, unopened.

This is only a few of the many, many playbills crammed into a magazine rack in the corner of the living room.

Chris’ grandmother’s bible. Chris was horrified when I took this down from the back of a closet. It was wrapped in an old plastic shopping bag. He was afraid that it being exposed now to the open air would ruin it. I placated him by wrapping it in plastic.

This is one of two old television sets laying around unsued and unconnected and also the aforementioned VHS player on stand by in case the first VHS player stops working.

Several archives showcasing Chris’ fascination with former first lady Jackie O.

Two Christmas trees and at the top of this pile are two kitchen tiles that are cracked and ususable that Chris will not allow me to throw out.

One of three menagerie of keys for unknown doors and locks.

The walker that Chris had to use when he came out of the hospital. Closeby is the portable potty that he used and, in another room he stores the oxygen tank.

Full Documentation Project

Full Documentation Project

Peter Erik Lopez

MFA

Transart Institute for Creative Research

May 11, 2020

Michael Bowdidge/David Antonio Cruz: advisors

Autonomy and the Archive in America

October 27, 2019

Currently, I have found my way into a project. The project is still in development. I did not quite understand what I was doing (I am using old family photos in the project). I was given an article to read titled “Autonomy and the Archive in America” by Lauri Firstenberg and some ideas from that article are helping me contextualize what it is I am doing. These are the lines I pulled from that article that best express my current project.

The idea of “unearthing narratives in historical archives” (313).

The idea of “min[ing the archives] for visual material and conceptual strategies” (313).

The concept that the photograph is an “unmediated and objective recording process” coupled with the idea that, in this project, I am looking to mediate the recording process of the photograph and make it subjective (313).

“The photograph functions as a sociological text, as evidence” (of what?) (313).

The archive as an “instrument of engineered spectacle” (314).

The concept of my creating a re-reading of the archive by “self-framing, reobjectification, self-staging, refetishization, and reversal” (314).

November 3, 2019

What are paintings supposed to do in 2019? How do they function? How does work on a canvas compete with installation art that moves and transmits, performance art that has at its center a moving or a screeching or a silent body?

I think we look to visual (painting on canvas) art to give us the same sensations as installation and performance and I think very few painters have come as close to doing this is Francis Bacon.

In Deleuze’s meditation on Bacon’s work titled, The Logic of Sensation, Deleuze explores many facets of Bacon’s paintings that prove Bacon is tapping into sensation. One only has to see a Bacon (the distorted figure, the semi-circular grounding of flat color—often orange or pink—the screaming pope encased, the meat and the bones on the crucifix) to recognize this.

I feel that I do not have this capacity (to tap into sensation) or, at least, it is not inherent in the portrait work that I do. Or, if it is, I am unaware of it. My work, I feel, is directly related to stories. When someone looks at one of my portraits, I believe the physicality of the subject (the dress, the skin, the pose, the furniture) should tell the subject’s story or the story of the sitting—which, itself, is often ripe with psychological Easter eggs.

But I have no clue what the reception of my portraits is to the viewer. Do they touch sensation and I am unaware of this? Do they, in some way convey the story of the person or the session?

The tricky part also, for me, can be expressed in a quote from Deleuze that suggests these two things are counter intuitive: “Sensation is that which is transmitted directly and avoids the detour and boredom of conveying a story” (32).

This art of avoiding boring people with the work is part of the work I think we are all doing as artists: how do we create work that speaks to people without shouting at them?

For instance, I had conceptualized an idea of painting the portraits of white people living in Harlem (gentrifiers) in their homes and titling the work with their addresses. When I was talking to a friend who is not an artist, he suggested the same message (or sensation) could be better accomplished with painting a white person standing below the Apollo theater. I tried to convey to my interlocutor that this sounded boring: the message was being shouted at the viewer and it loses the opportunity for sensation. But my friend insisted that this was the better way to go.

I am starting to understand that sensation (and story) are best conveyed through a trusting of one’s instincts and through a spirit of experimentation and balancing one’s work between the story and the sensation.

Currently, I am appropriating the archives of my family album and working strictly with sensation to tell stories or to tell truth. I do not want to speak to much about he project because i do not want to fall into the trap of producing work that is flat and boring. The work speaks to family, family roles, inheritance, history, memory, truth, and mythology.

November 9, 2019

The process for this latest set of paintings is difficult but I am enjoying the challenge. The genesis was the goat painting: the painting I did of myself as a child on the beach: the painting where I could not get myself to paint my own face as a child so I painted the face of a goat (when thinking about the significance of the goat I must admit that there is no symbolism behind it. What happened that day that I was painting myself as a child was pretty much the same thing that happened in the origin story of the Hindu, elephant-headed god, Ganesha: One day the goddess Durga was bathing. She did not want to be disturbed so she created a guard for the door out of flakes of her skin. Durga’s husband arrived and, having been stopped at the door by this guard, the god of the Himalaya, Shiva, blasted the guard’s head off. Durga was distraught—the guard was like a son to her, created by her. In a panic, Shiva ran out to replace the head of the guard. The first creature he came across was a baby elephant and that is how the elephant-headed god of India was created…and that is how my goat-child was created. Unable to paint my own face as a child because of trauma, I looked around and the first thing I saw was a painting I had done of a goat’s head while in India).

I had decided that if I was going to explore the trauma, and the idea of memory, the best place to begin was an old family photo album. I chose some old family photos (many with myself as a baby or a child) to use, to change, to reconstitute. Sometimes i could clearly see how I would alter the photographs in an oil painting rendering of them. Sometimes I would have to lay the photographs out and stare at them, walk away from them. I always tried not to go with my first impulse in how I would alter the work. I had to think about it, walk around with the idea, let it percolate to measure if it felt honest or contrived.

The memory and the truth I am exploring revolve around many themes: sin, inheritance, Aryan culture, sex, race, parenthood, marriage, abuse.

Gerhard Richter

November 24, 2019

The image here by Gerhard Richter reminds me a lot of how I am working with photographs in my project about memory. Richter’s process makes his photographs have a blurry quality to them. There seems to be a statement here of time or permanence. I am also attempting to discuss time and permanence but through image and memory and symbolism (perhaps a touch of surrealism). I am also very attracted to Richter’s sense of composition. His figurative works are neatly composed. But the neat composition combined with the blurring effect give his work dark undertones.

The blurriness is in full effect in this piece and the monochromatic quality to it is reminding me of how I am working with paint for my memory-project; before I begin each composition, I am laying down a foundation of gray and painting over it while the paint is still wet. I have to work a bit harder to work up the colors, the blacks and the whites in the pieces I am doing but it is giving those pieces the same monochromatic effect I am loving here in Richter’s work. Looking at this particular piece, it occurs to me that these works are about ghosts or about hauntings and I believe that the photographs from an old family album that I am choosing to treat in my paintings (or maybe, the photos that are choosing me) are about the things that haunt me: The specters that wander my subconscious.

This Black and white Richter image has me thinking about going deeper and further back into the family albums. Particularly the albums of my German mother and begin meditating on the images of her life before I was born to see what ghosts emerge.

Marlene Dumas

November 16, 2019

After seeing the direction of my latest group of paintings, my adviser, David Cruz, requested that I look at two artists who he said he sees similarities with in my work. They are Marlene Dumas from South Africa and German artist, Gerhard Richter. I took a look at the work of both artists online and chose three works for each that both caught my attention and works where I could also see a connection to my current work. Here I will present the three from Dumas that I studied. Next week I will address my Richter choices.

I was immediately attracted to this piece primarily, I believe, because it is a portrait. But the style is also very much like the style in which I am using paint for this series. The paint is applied thinly and there is also aspects of the composition (the hands, the collar) that are outlined. Elderly women also play a heavy role in my work right now because I am mining old photographs from an album and many of the pictures record the older German women from my childhood. In both my work and Dumas’ above portrait, the women have a witchy-quality to them which I find interesting because when my mother began telling me the story of her life one day, she began at the Bavarian mountains where she reported that it was rumored witches lived.

This work by Dumas attracts me because of the pairing of a human portrait with an animal’s head. Of late, I have been playing with self-portraits and goat heads and while I have abandoned that path, the new work does include a child with goat eyes, animals, and I am planning to replace the head of a subject with an animal’s head for one of the final pieces. Even before my work with goat heads, I have always been attracted to art that combines animal imagery with human anatomy. I believe this may have sparked from my childhood fascination with Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons.

This Dumas portrait has a dark quality. There seems to be something strange or off about the person presented here. There is also a strangeness and oddity to the vignettes that I am painting. There is something off about each scene that seeks to touch the sensibility of the viewer in a way that disturbs but holds them. I see this quality in the above Dumas portrait. Again the quality of the paint is thin and outlines are prevalent.

What's In a Number?

December 1, 2019

I have seven pieces.

Seven pieces that deal with memory.

Memory recast.

Reshaped.

Reconstituted.

An exploration of truth through symbols, through juxtaposition, through totems, through surrealism.

Seven is not enough, I feel.

There is more to be mined. More to be said. More truth to be explored.

But I am stuck.

The images are yielding no more than seven.

I will stare at the photographs some more tomorrow.

And then put them away.

And then stare some more.

Something will come.

And I will have eight.

Personal Mythology

December 15, 2019

In my current project wherein I am reconstituting old childhood images (that project the memories of my mother, my sister, my step father, step brother, aunt, grandmother, and father) I am attempting to assign these images meaning as symbols of personal mythology.

According to Joseph Campbell, “myths are clues to the spiritual potentialities of human life. Myth is the experience of life and they teach you that you can turn inward” and there you begin to “get the message of the symbols”.

Campbell in The Power of Myth bemoans that we seem to have lost the importance of the old myths (the Greek myths, the Biblical myths, Native American stories, etc). He claims that kids today make their own myths as a result and “this is why we have graffiti all over the city”. While I am attracted to the idea of these marks as evidence of personal mythologies (like today’s Facebook pages where kids are creating their own mythologies through curated images and videos), I am more interested in the societal aspect of mythology that is lost; Campbell asserts that mythologies teach us how to “behave in a civilized world” and I contend that they also teach us about the world.

As such, it is my contention that popular and ancient mythologies pale in this job next to the mythologies of our childhood.

There is no substitute for learning about woman than your mother.

King Priam can not teach you the pain of loss the way a stepbrother may.

A serpent in the garden cannot teach you the concept of deception the way a boy who is trying to fuck your sister can.

In this vein, with this project, I am attempting to imagine my own childhood mythologies and the stories, the traumas, the lived lives, of those around me and how all of their ways of navigating the world impacted and shaped the way I live in the world.

As writer or recorder of my own mythology, I identify as the shaman versus the priest (as distinguished by Campbell).

“The difference between a priest and a shaman is that the priest is a functionary and the shaman is someone who has had an experience”. Further, “the person who has had a mystical experience knows that all the symbolic expressions of it are faulty”. This concept is important to my work. As I sit over the images and meditate, it is only when a symbol appears that blurs the experience that I begin working. It is very important that my mythology is not spelled out. “The symbols [should not] render the experience [but] suggest it”, according to Campbell.

If you haven’t had the experience, Campbell asserts, how can you know what it is?

Mexico City and Beyond

January 20, 2020

It was unfortunate that I couldn’t but I feel that I had visited that city 11 year ago and was able to see and study a lot of art. Though I could only stay with the program briefly this year, it was a very positive experience.

One of the highlights was a your of the Anthropological Museum with artist, Eduardo Abaroa. Eduardo’s in depth knowledge of Mexican history made the visit to the museum all the more special and inspired me to think about some of the mythology we discussed as fuel for future works.

But the greater moment for me was my presentation and the reaction to the work I brought with me.

When I came to Transart, I did not know where and how I would fit in with the program and with the art world at large. I “just” did portraits in a world that seemed to reject any work that was not political or performative. “Make a video” was the Transart motto if all else failed and I even struggled with that.

By the Winter Residency of last year, however, the program found artist David Antonio Cruz as an adviser for me and that began to turn things around. In one studio visit, David inspired me to explore materials, size, juxtapositions (without ever asking me to stop painting portraits).

Then, in Berlin, Michael Bowdidge’s “Becoming Animal” classes inspired me to reveal a nine-year old self portrait I had done—exchanging my little-boy face with a goat face in order to subvert trauma I had experienced as a child. Additionally, Michael’s class inspire me to act out that trauma with fellow classmate Kate Hilliard that unlocked something I was afriad to look at.

As a result of David opening my mind, and Michael opening up my past, I was able to do work I had never thought capable of and the apex (so far) is the work I brought to Mexico City which are the reworked family photos I have been blogging about for the past few months.

The reaction in Mexico City to the presentation of the work and the work itself was overwhelmingly positive and it felt wonderful that my work was connecting in some subtle, haunting way with an audience of artists and curators. I felt like I had arrived at where I was supposed to with the program.

As we wrap up this final year of the program (with a process paper and a grad dialogue) I am beginning to think of what happens after Transart.

What’s next?

How do I continue?

How do I take what Transart gave me and keep that momentum going?

How do I continue to be, to become an artist?

Working on it

February 16, 2020

Since coming back from Mexico City in early January, it has been difficult to get moving but I am still making slow progress towards the process paper and cleaning up the pieces I showed in Mexico City.

For the paper, I have been studying the work of Gerhard Richter with whom my family-photo project has a lot on common. The descriptions of his work and process are giving me a new language through which to describe my process and aims.

My studio advisor, David Cruz, has persuaded me to think about the presentation of the pieces which I will re-present in Berlin. My original presentation was just tacking the pieces on a wall and allowing them to be shown with their rough border and the canvas’ roughly shorn edges. But in conversations with David, I have come to understand that if I am working from photos and conceptually, riffing off photos, the presentation should resemble photos.

Because of the busy nature of teaching and because I am the union representative this year of a school wherein the principal enjoys breaking the contract, it has been difficult getting all of the above accomplished but little by little I am getting there.

Framework for Grad Dialogue

February 29, 2020

Framework for Grad Dialogue

Peter Lopez and Syowia Kyamb

In her article, “Autonomy and the Archive in America”, director and curator, Lauri Firstenberg, discusses ways in which the contemporary artist works with archives. Firstenberg describes the process of many artists working with archives as the artists attempting to “unearth narratives” and “min[ing the archives] for visual material and conceptual strategies” (313). This is the work that I am attempting with the project I have titled, “Her Family Album”.

“Her Family Album” is a body of work that consists of eleven paintings that use the family-album-as-archive and using that archive as its source material. In this work my goal is to restage photographs from a photo album gifted to me by my mother (and carefully curated by my mother) when I was eighteen years old before she would leave me in New York so that she could live in Florida. The visual material I am lifting from the album are images of myself as a child, my sister, my mother and my grandmother. In each of the eleven renderings of the visual material I have selected, I am inserting symbols (demons, animals, bodies) that seek to recalibrate the image of the happy family photo in order to represent something closer to the true experience of my childhood memories: memories steeped in sexual abuse and tinged with the weight of being the direct descendant of a Nazi soldier.

The concept for the work is how the individual memory can establish dominance over the power of the public archive.

Thematically, in the performance titled, “Kaspale’s Playground”, Syowia Kyambi is similarly working through the concept of how archives serve to domesticate the past and how memory can serve to thwart that domestication.

Syowia has created a trickster-specter called Kaspale who haunts archives (sometimes physically, sometimes from great distances) in order to establish the dominance of memory in places where archival interpretation serves to define those spaces in fairer, more benign terms than individual memory would have them defined.

Her latest work tackles the memory of an era and a facility; it is the memory of the twenty-four year rule of recently deceased President Daniel arap Moi of Kenya and the facility he used to torture dissidents in his attempts to consolidate power called Nyayo House. According German news organization, Deutsche Welle, the former president’s official funeral leaflet described Moi as "an icon, a legend and a philosopher.” This power of the archive to calcify impressions is what Syowia is speaking to and, through her performance with both a Kaspale mask and a Kaspale puppet, is attempting to surface and for lack of a better term (but one appropriate for the title of the work) to “play” with—or to play through.

In “Autonomy and the Archive”, Firestenberg lists a number of terms that one can use to name what it is that the contemporary artist is doing with archives; some of those terms are “self-framing, reobjectification, self-staging, refetishization, and reversal” (314).

Both “Her Family Album” and “Kapale’s Playground” seek to self-frame and reverse the archive in the cause of the struggle for the independent memory to not be drowned out by the archive’s attempt at creating a shared public memory whether that attempt be through the (re)writers of Kenyan history or through a parent struggling with a troubling past and a complex vision of motherhood.

MCP506 Final Paper

I

When I was a child my mother would tell me the story of the time she took me to Coney Island as a baby because my father was yelling at her to keep me quiet. She says she stood at the boardwalk staring at the ocean with me screaming in her arms as I had been doing for hours. I don’t know what her face revealed, what intentions were there to be read, but a black man, she says, who was sitting at a nearby bench, said to her softly, “don’t do it, lady”.

Brooklyn

In the last year my studio space has changed somewhat drastically. Since I moved into my partner’s Brooklyn apartment, my studio space is smaller, sparer, and stranger. In Queens, where I lived alone, my whole apartment was my studio so my portrait work had the run of the place. I had my sittings perch on my wine-colored futon, or lay on the deep brown covers of my bed, or sit on the red, yellow, and orange geometric-patterned rug on the floor. There, in my Queens apartment, I arranged things that were in the room around my sittings. For Michelle, I placed several pottery pieces at her feet with a dagger sticking out of one of the pots. For John, I laid a katana across his reclining body. I surrounded Jasmine with books and then ripped pages out of one book we selected together, scattering the torn pages around her. I arranged pink and white carnations around Caleb that I had plucked out of a vase on the windowsill.

Now, here in Brooklyn, a small back room serves as my studio. My portraits in this room are stark compared to the ones done in Queens. My sittings have only room enough to sit on a small, skeletal chair in front of a white, yellowing wall or recline on the unpolished wood floor. I try to dress the portraits up with a plant at a sitter’s feet, or a blue shawl across a shoulder. The portraits are not the same here in Brooklyn. The color is gone. The people who come to sit are wearing white. Like spirits.

Before I moved in, my partner Chris used this small back room for storage. In this room, he stored the clothes of the three dead matriarchs who raised him. He stored his now grown son’s toys and a small bed frame, a bookshelf full of crumbling paperbacks, a dresser full of old bills, a newspaper with a headline reporting the assassination of JFK. It is a room for ghosts and dusty memories. So it is no wonder that my practice has turned to memory and specters.

The process with which I am working with memory is complex and haunting.

Years ago, my mother put together an album for me consisting of family photographs mainly capturing my childhood. The pictures are 33 millimeter photographs stuck behind cellophane pages in a Disney-themed photo album. In my process, I leaf through the cellophane covered pages and select images. The criteria, at first, seemed to be interesting and balanced composition. But I soon realized that was not the criteria with which I was selecting images. My true criteria, I realized, was that there had to be room in the composition for an insertion. Not just physical space in the composition, but room for me to exorcise childhood impressions and illustrate childhood stories by inserting symbols, alterations—ghosts. The chosen photograph had to summon in me a story not being told. Having selected a photograph, I would then paint a replica of the family-photo image on a swath of canvas and include a somewhat non-analogous, apparently unrelated entity within the composition. The additions, in fact, are not random or unrelated to the actual photograph, however: they are (to me) symbols of truths that hover just above the happy and warm family photographs.

Life Under Water

The path to this project is somewhat unclear. It wasn’t something that was suggested and it wasn’t something that I had ever previously conceived of. In fact, I regarded the use of photographs as a reference for painting as something of a cheat at worst and a somewhat meaningless activity at best (why, I thought, recapture a moment in paint that has already been captured in a photograph?). This is why I have always fashioned my portrait work after Lucien Freud and Alice Neel—portrait artists who both worked solely from live sittings.

Still, I have also been drawn to the work of Francis Bacon. Bacon’s work always seemed to me to offer another avenue in which to work with the figure. His work took on both abstract and surreal aspects and Bacon worked largely from photographs, sometimes referencing them directly, sometimes folding them and using the distortions of the folding as visual reference.

While Neel and Freud chose to ignore the death knell of figuration with the advent of photography, Bacon seemed to understand that photography (the tool with which one could now easily capture composition, landscape, portraiture, and moments) turned painting into an “aesthetic game” (Deleuze 10).

II

My sister was marched out the door. She was 16 or 17 and pregnant again. I remember the look on her face as she followed behind my mother; she was angry, resentful. My mother, I’m sure, believed she was saving my sister from a mistake—that she was freeing up her life for better things.

My sister never went to college. She never learned a skill or became famous. She barely ever held a job; she instead stole someone else’s husband who then physically abused her for ten years and she would later almost die from a staph infection because she couldn’t afford health care.

Sensation

In his book on Bacon and Bacon’s works titled, The Logic of Sensation, Deleuze points out that Bacon (like all figurative artists post-photography) now had to deal with “sensation” over figuration (31). As a portrait artist, myself, there are times when I am thrilled with the work I have done but there are just as many times where I wonder at the point. That is not to say there is no sensation in my portrait work. There is—for me. But I wonder if the sensation goes beyond the portrait artist and the sitter for anyone in 2020. I, myself, experience sensation in the work. But does anyone else? Or is the work a bit masturbatory?

Take my latest portrait of Andres, a local NYC actor and writer; I look at the portrait and I still experience the sensation of what it took to paint the portrait of Andres: the preliminary request and scheduling, the negotiation of positioning, the thrill of becoming familiar with the actor/writer over the course of the four to five hour sitting, the struggle with color and changing light, the rush of time and all you’ve managed is half a face, the after-sitting dinner and drinks, the days of reworking, the sharing of the final product and the emotional reaction of the sitter when he sees it. In the microcosm of myself, Andre, and our close friends and family, there is sensation in the work.

But does that sensation exist outside of the experience of the artist and the sitter?

That is the question that I have tacked onto my portrait work: the type of work to which I seem to have always been attracted and anchored.

But in last summer’s Berlin residency for Transart, I was determined to explore something—anything—outside of portraiture. I was determined to explore sensation outside of portrait work to see if I could expand sensation beyond artist and sitter.

Andres

Becoming Animal

In Michael Bowdidge’s course in Berlin (titled “Becoming Animal”), I presented an anthropomorphic painting and a performance that explored personal trauma. I had never before wanted to delve into memory or trauma because it always seemed to me both gratuitous and unnerving. Both of my Berlin presentations (the painting and the performance) revolved around childhood sexual abuse: An abuse that was sanctioned by the blind eyes and the deaf ears of adults whose minds could not cope with the suggestions they were receiving, could not read my outbursts for what they were reporting, would not decipher the language of a young boy whose older step brother’s actions made him break windows with his hands.

I hadn’t known it at the time but these presentations in Berlin must have opened a door and opened my senses. The experience of presenting a trauma did not influence me into making work detailing this trauma necessarily. I did not know what I wanted to do after Berlin actually. But like a calling, I was pulled to the old photo album that recorded images of me as a child at the age of or around the age of that trauma. I examined the 33 millimeter photos arranged by my mother (an album that seems to have conveniently left out any photographs of my step brother) and something would come: a symbol to be inserted that would, in some way, reveal the language of a young boy who had no voice; a symbol that would reshape the images in a way that felt more honest: work akin to Martin Luther’s 95 Theses nailed to a church door—changing things—casting light.

And this, perhaps, was the beginning of touching sensation for me.

Francis Bacon’s figurative work released sensations in a number of ways: the colors, the melty-fluidity of the figures, the geometric encasings. But the characteristic of Bacon’s work that most closely touches my work with these photographs is his insertions.

Take Bacon’s 1973 Self Portrait; sensation comes from all of the elements listed above but my contention is that one of the strongest conduits of sensation stems from the insertion of non-analogous elements into the composition: it is the sink and the overhead light fixture that jars the viewer into a feeling. They do not belong there. We do not sit in bathrooms dressed this way, in this posture. In literature, this phenomenon is called absurd realism. In absurd realism, authors combine absurd elements with realistic elements in an effort to create an overstated sense of reality. In Self Portrait, it is absurd for the figure to be leaning on a bathroom sink floating in space. Is the sink a symbol? For the viewer, it most certainly is: it speaks of bathroom, cleaning, water, mornings, tile, plumbing, family or solitude. For Bacon, in this piece—who knows what it represents? And our certainty combined with the mystery of his meaning is the cause of sensation. Absurd realism in paintings jars the viewer into a heightened sense of things because the mind wants to decode what it is viewing.

I found, as I began working through these photographs that the symbols or insertions did not solely speak of sexual trauma; it was deciphering the larger world around the younger me. The symbols I was inserting into the composition of the photographs (often animal) read as decoders of a mythology I had both lived as a child and repeated to myself over and over as an adult (like an epic poem) resulting in something closer to sensation than anything I had ever done before because much of the symbolism I was using derived solely from “involuntary memory”.

Deleuze cites Proust when unfolding how involuntary memory operates. According to Proust, involuntary memory “couples together two sensations that existed at different levels of the body and that seized each other like two wrestlers, the present sensation and the past sensation, in order to make something appear that was irreducible to either of them, irreducible to the past as well as to the present” (57). This in fact seemed to me to be exactly what the process of painting these family photo pieces were: a collision of childhood memory and the way adults build a personal mythology around those memories. This collision gave life to this body of work that belonged wholly to neither the past nor the present.

First Encounter The Snake Was Allowed to Stay

Living Room Recital

Mythology

There are two ways through which I am working with the photographs from my childhood album. There is memory and there is mythology. I do not use the term mythology referring to Greek or Roman myth or the idea of make believe. Mythology is a term I am using to describe the psychological way in which we, as children, make sense of the world around us through the stories we are told and the stories created by our experiences and how, as we age, those stories calcify into the story of our lives. In my work, I have chosen to represent the mythology I have created through symbols. In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell states that “myths are clues to the spiritual potentialities of human life. Myth is the experience of life and they teach you that you can turn inward” and there you begin to “get the message of the symbols”(5).

This idea about myths may best be explained using another subject. My partner, Chris, is a good example of someone who has built up a personal mythology based on the stories of his past and the stories told to him by the three matriarchs who raised him. Chris tells (himself and anyone who will listen) the same stories over and over again. And if you are around him long enough, you see how these stories, these mythologies, shape the way he navigates the world today.

When Chris was twelve, while playing in the backyard, his beloved dog mauled his little brother with no provocation. His little brother was rushed to the hospital. The blame was lay squarely on Chris and he was threatened to be banished from his home. His dog was put down.

I realize that anyone who hears this story simply files it away under “trauma”. But I argue that Chris (both as a man and as a child) has built a personal mythology around this story and that this incident acted as a chapter in a myth wherein Chris learned the shape of the world he lived in: the terror of the unexpected, the sadness of losing a loved one, the heavy weight of blame. Today, as a man, Chris reacts strongly against blame. His mythology of the world is that the world seeks to scapegoat him for things he cannot help.

It is not blame that shapes my mythology but rage and shame; I experienced rage for the first time in my life through my step brother. But it is important to understand (in order to understand how I am using mythology here) that the sensation of rage cannot be separated from the story (the mythology) of my step brother and our relationship: of the nights in our room, of the days we walked together, of the shame in my stomach for what he was doing, the love in my heart for him, and the complex mystery of his motives. My step brother does not physically appear in the work. He cannot. My mother edited the album tightly. But he appears as symbols. He is the snake in the bed and the demon greeting the baby. He is lust that a child is not prepared for but is not adverse to. In the way that Zues takes the shape of a swan, a golden shower, an eagle, and a bull, my stepbrother takes many forms in my work. The symbols are absurd juxtapositions that should, I hope, jar the viewer (or the reader) into discomfort and short-circuit their ability to code so that their minds are forced into simply receiving the sensation that the image projects.

But as noted earlier, the work took on more themes than just step brother and sexual abuse. Aside from my own experiences, my own mythology, I was witness—in close proximity—to the lives and the stories of my mother and my sister. I knew the smell of their menstruation and the sound of their tears.

As a result, with this project, I am attempting to imagine my own childhood mythologies and the stories, the traumas, the lived lives (the extended mythologies) of those around me and how all of their individual ways of navigating the world impacted and shaped the way I lived (live) in the world. How could it not? The stories we are told as children and the stories we live through must become nothing else if not mythology: how does a child’s mind deal with their own navigation and the surrounding needs, desires, and sadness of the people around him, pressing on him, unless he makes them into stories or a form of anecdote that is cut off from who he becomes as a man? In this way, I can liken my work to children’s drawings that seek to simplify form and flatten out reality (perhaps as a way of getting to truth). In my photo album paintings, both the child and the man are at work (two wrestlers colliding) but instead of flattening out the truths (mommy, daddy, house) I am choosing to reconstitute the images through symbols not easily read. For, according to Campbell, “the symbols [should not] render the experience [but] suggest it”(72).

Images of children’s drawing depicting domestic violence

III

I woke up to the sound of my mother wailing in the other room: the living room that she used as her bedroom. I snuck out of my bed and walked along the shadows of the walls following her moans and her cries. She was on the floor on her knees and the Black man who was before her was stoically staring down at her. I could smell the liquor from where I stood—a small boy in the shadows.

My mother brought many Black men home. Sometimes she would wake my sister and I so my sister could play piano or sometimes she would wake us because the man she brought home had brought us food.

I knew this man who my mother was kneeling in front of: Willy. He was very kind but in this moment, he was not being kind to my mother. He was tired of her. He wanted to leave. He was trying to leave her.

I went back to bed recognizing that I could not help her. The pain he was causing her was not physical. Many years later, I found out that Willy was a married man. My mother was an affair. She told me that he was the love of her life.

Memory

The Descendants

In Mark Wolynn’s book titled, It Didn’t Start With You, Wolynn examines something akin to cellular memory as relates to family trauma. I became interested in connecting Wolynn’s idea to my work with family photos once I realized that it was not only my own trauma that I was excavating and exploring but the trauma, memories, and mythologies of my sister, my mother and quite possibly, my grandmother.

As I pulled one photograph after another off of the sticky pages of the album, inspecting each one and determining if there was something there for me, I was haunted by one particular photograph of four children sitting in a row on the living room floor. They were myself, my sister, and my two cousins (children of my mother’s sister). At once, it became inescapable to me that these four children were the descendants of a Nazi soldier. I had known the stories of my grandfather as a Nazi soldier at a very young age; older black and white photographs showcased him in that unmistakable uniform with the unmistakable armband. It was at the moment that I took up the photo of the four children that I realized what I was pulling from the pictures was more than my own childhood mythology, traumas, and sense of the world. I was digging at the truths of my mother and of her mother and I was touching a trauma within myself (a part of me and apart from me) which belonged to those two women and their connection to the event that shook the faith of the world: the Holocaust.

“Emerging trends in psychotherapy”, Wolynn writes, “are beginning to point beyond the traumas of the individual to include traumatic events in the family and the social history as a part of the whole picture” (17). Wolynn’s work attempts to prove, scientifically, that “traumas can and do pass from one generation to the next” (19). In his book, Wolynn seems to allude that the Holocaust was the mother of all traumas (though I would argue that Africa American slavery and many other genocidal events compare). Many of his theories revolve around the trauma of the Holocaust survivor (how descendants of Holocaust survivors are born with “low cortisol levels” similar to their Holocaust surviving parents) but in my work, I am interested in the trauma passed down from the descendants of Holocaust participants.

My grandfather (right)

My mother talks of her Nazi father as a reluctant soldier: A man who was loving, charming, and warm; a man who drank and laughed; who played the piano and sang; a man who was only following orders. She paints her own picture of the memory of her father as kill-or-be-killed and imagines her father’s participation in genocide as a way of protecting his family. My mother’s trauma (and quite possibly the trauma of her own mother) (and quite possibly a trauma passed down to me) is one of avoidance and reconstitution.

It must have been painful being raised on the wrong side of history. It must have been tricky to love and defend a father who was a participant in one of humanity’s darkest moments.

Wolyyn asserts that I do not have to directly experience this trauma in order to “carry the physical and emotional symptoms” of it (20). My paintings from the photo album are violent and sexual and at times they are both. In the images I alter, children are faced with danger and with situations to be avoided and reconstituted.

In one of my pieces, my mother holds a baby (me) whom she is unable to love because of his deformity. The child is born with the eyes of a goat. He is the physical scapegoat for the sins of her father. He is World War II nuclear deformity. He is the death of God as reported in TIME magazine or he is the Adversary. A tear rolls down her cheek but she keeps a straight face. Avoid and reconstitute.

When my mother and step father sat me down and demanded to know why I was acting out, I did not have the language to tell them what my step brother was doing, alternately, to me and my sister. Later I would reconstitute my brother’s actions as the actions of a confused teen feeling unloved by his father, my mother’s actions as a way for a mother to manage what she knew but could not manage.

Because my mother’s trauma exists on a cellular level within me, the presence of her past leaks into my work: She sits naked at a children’s birthday party while a hawk picks apart a freshly killed dove and children absently eat a white cake.

Birthday Party

Engineered Spectacle

My mother has a small bookcase in her Florida home stacked with photo albums. The photographs inside have followed her from Germany (recording her childhood and her family) to Virginia (recording her first marriage to a poor American soldier) to New York (recording her second marriage to my father) to Florida (where she lives now). Photographs are important to my mother. Even now if she sees a picture my sister or I post on Facebook that she likes she will send a message: “can you send me a hard copy of that”?

My mother is an archivist. So the lion’s share of the photographs in her albums are either taken by her or (one can feel) directed by her. My mother has a vision of herself and an idea of family life that is staged throughout these albums. It is characteristic of the family-album-as-archive: selective memory.

No one cries in my mother’s albums. No one dies. No one slaps women across dining room tables in her pictures. There is no incest. There is no genocide.

In Lauri Firstenberg’s article, “Automomy and the Archive in America”, the author posits that the archive is an “instrument of engineered spectacle” (314). She discusses how contemporary artists have “unearthed” the “cultural and political narratives residing in institutional archives” and how contemporary artists have “mined” these sources for “visual material” and “conceptual strategies” (313).

Photos from my mother’s photo albums

Some of the conceptual strategies Firstenberg discusses are “self-framing, reobjectification, self-staging, and reversal” (314). By taking photographs out of the album that my mother curated specifically for me, it is my intention with this project to reconstitute the images in a way that sort of backfires on the intention of the family-album-as-archive (look at how happy we are; look at how many great moments we have had) and instead serve to disrupt the illusion of my mother’s narrative with mythological symbols representing (the truth? My truth?).

Second Encounter Wedding Day

In order to accomplish this, I needed to engage with the family photos in both a subjective and objective way.

I have explained the manner through which I worked with the photographs subjectively in terms of memory and mythology. The objective process came by looking at these photographs and working with them very closely to the way Gerhard Richter worked with photographs in the 1960’s.

In Virlag Hirmer’s book on Richter’s work painting from photographs titled, Images of an Era, Richter reveals that he “wanted to do paintings that had nothing to do with art” and this is the reason, he stated, that he started working with photographs (13). Richter treated photographs as readymades and found-objects that he hunted for in the magazines of the day. Although my source for material came packaged in one album, it was still (like Richter’s process) a hunt. I went at hunting for source material in this one album with no set narrative in mind; though I was reconstituting my mother’s arrangement of the past with a sense of my own mythologies and the mythologies of my surrounding family members, I did not look for photos that spoke only to my experience or to the experience of myself and my sister. Nor did I choose photographs solely of my mother.

As stated earlier, what mattered in these found objects was that there was room for an insertion of truth, of a symbol that carried with it a story.

Moreover, in working this way (reworking photographic material), I managed to free myself from the burden of making art or making a painting because I was engaged more in the reconstitution, the self-staging, than I was in making art. Hirmer reflects on Richter’s work with photographs and states that Richter’s reframing and refocusing of magazine photographs availed Richter of the “truthful” (now so aptly captured by photography) (14). In opposition to this, my work with family photos allows me to find and express something more truthful than the “truth” of a photograph. With the insertions (a naked black man, an eel, an aborted fetus) I hope to force the viewer into a kind of hyper-seeing wherein they have to navigate and negotiate the presence of disconnected imagery interacting in a happy-family-vignette without any clues that help decipher the intrusions. They are left with only sensation.

Works by Gerhard Richter reconstituting found photographs from magazines

Though it was suggested to me that I could accomplish the same work with digital manipulations of the source photos, I knew from the start that I wanted the work to be paintings. I am a painter. And so I thought it was really important that my final Masters project be in the medium that I work in.

Unlike Gerhard Richter who used paint to scale up magazine photos, I chose to scale the paintings down. I worked organically, never choosing a specific size to stick to for each piece (they are all round about 6”X8” or so). Once a few pictures were selected, I would stretch a canvas large enough to fit 4 compositions (in any way they could fit as long as there was border enough to cut them apart from each other).

To create more of a vintage feel, I desaturated the colors I was using by preparing a 6”X8” surface area with grey paint first and then rendering and reconstituting the image of the chosen photograph while the grey was still wet so that it would absorb and mute the color.

When I showed the first few pieces to my advisor, David Cruz, he immediately recognized two things that needed adjustment; the first thing was that for each of the pieces, I was not varying my brushes. I cannot say this was an artistic choice nor was it for lack of brushes. What I recognized was that I was so immersed in producing the work that the manner in which I was working escaped me. It was almost as if, possessed by what came to me to insert as a symbol, I was in a rush to give the image life on canvas; I found I was not creating as much as I was exorcising. This was also made apparent in David’s second criticism that I was moving straight to paint without first sketching the composition.

Though varying my brushes proved to move the work by resulting in a more delicate image that made the pieces all the more haunting, sketching the compositions beforehand was not feasible. Using still-wet grey paint as a base did not allow for sketching before painting. Nonetheless, I am happy with the results.

The last obstacle was presentation. Like the execution of the work, I was so caught up in the psychological aspects that I did not think about how the pieces would be finished or presented; I simply separated the canvas from the stretchers and then (with four images sitting on one canvas) I would cut out each finished piece leaving ragged, uneven two to three inch thick borders.

David was horrified.

He insisted that I find a different, more finished way to present the work and he showed me a series of small paintings done by a former student of his who was also using photographs as source material. His student presented her work as Polaroid pictures and so her finished pieces were the exact size and squared off area of Polaroid pictures including the white borders we associate with them. As of this writing, I am currently refinishing the work with straight edged white borders so that an audience can associate the paintings with the source material which is photographs.

At its conclusion, this project has me thinking of expanding the concept into my mother’s personal archives and experimenting with the black and white photographs she has collected of her life before I existed. I have had two separate sittings with my mother going through these albums as she narrated her life, her loves, and her traumas with me. I also have her life documented in writing; years ago my mother believed that she was going to die. There was an aneurysm in her brain. My mother is terrified at the thought of death. To try and get her mind off of her situation and off of the thought of death, I asked her to write her life story for me. I will use her writings as inspiration to reconstitute her archives in attempts to get at a deeper truth than what is being presented in the albums she has compiled of her life. I am looking forward to, myself, indulging in the sensations released from the work.

IV

I remember sirens, every night, sirens. My mother was in the volunteer Red Cross during the war. We slept in our clothes so that we were ready to go into the bunkers, mostly at night during the attacks. I remember stepping over dead people on the way to the cellar (bunker) I remember screams. I remember one time my father too was in the bunker (most times he was not there, maybe at "work"). I remember he slapped a man in the face, later I heard he did this because the man, also living in the same building was in shock with fear.

-excerpted from my mother’s memoirs

V

We were out on an assignment. He was a senior in high school and one of his teachers assigned the students to collect anything that had a Greek name to it. I surmise now that the concept was to show how prolific Greek culture was inside American culture. But back then, I had no idea why my stepbrother had to do this. I only knew that he asked me—me—to go with him. I loved him.

Bibliography

Wolynn, Mark. It Didn’t Start With You. Penguin, New York, 2016.

Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. University of Minnesota Press, 1981.

Campbell, Joseph. The Power of Myth. Anchor Books, New York, 1988.

Firstenberg, Lauri. "Autonomy and the Archive in America: Re-examining the Intersection of Photography and the Stereotype." Against the Archive: Toward Interdeterminacy and the Internationalization of Contemporary Art. (2006): 53-91. Print.

Schneede, Uwe M. Gerhard Richter: Image

Mother

“Both my siblings were born in Saalfeld, our mothers home, I was born in Nordhausen/Harz (the legend goes that there is a mountain where witches were burned in the Middle Ages)”

This is a line from my mother’s memoirs.

Nine years ago, my mother was diagnosed with having an aneurysm in her brain. She believed it was going to burst at any moment and that she was going to die. My mother is terrified of death. So, to take her mind off of her condition, I had her write her memoirs for me. I would have to read it in its entirety to remember what she highlighted about her Nazi father, he domineering mother, her sadistic Hitler-youth older brother, and her troubled younger sister who chronically ran away from home. But the line above—the line where my mother cites her birthplace at the base of a witch-mountain-grave always struck me.

Probably because there is and has always been something witchy about my mother.

She has premonitions. She knows things. She feels things. She is mean. She is violent. She was sexual and seductive well into her 40’s and 50’s. She surrounded herself with laughing women and booze. And many men.

She was powerful.

After spending sometime reconstituting images from my childhood photo album (images of my childhood that were weighted by the shadow of my mother), I decided to begin working on this project using photographs of my mother in her youth.

Thematically, I am running with the connection between my mother and witches.

As a student of literature, the idea of witches brings to mind s variety of passages and images.

Circe and Odysseus’ men tuned to pigs.

Young women levitating and dancing with the devil in Arthur Miller’s Crucible.

A few things will be different between this project (my mother’s photographs) and the previous (my childhood photographs)

Technically I am making them differently. For my childhood photos, I painted the photographs as though I were painting a portrait: I looked and replicated on canvas to the best of my ability. For my mother’s photographs, I want to rely less on my eye and focus my energies on storytelling, interpretation, and reconstitution so I am tracing the images from my laptop onto tracing paper, running lead over the opposite side, and then transferring the image to canvas by retracing (with whatever alterations I nee to make).

The color is different also. My childhood painting were heavy and I wanted to weigh them down by painting over a gray base, washing out the color. With my mother’s photographs (though they are older and in black and white), I am being more crisp, more vibrant, more exact.

Because this is the witch in her prime. Dancing with the devil. The witch pre and post World War II. Before she began losing her power to the American dream and to cheating and to violent men.

MCP506 Draft Paper

I

When I was a child my mother would tell me the story of the time she took me to Coney Island as a baby because my father was yelling at her to keep me quiet. She says she stood at the boardwalk staring at the ocean with me in her arms screaming as I had been doing for hours. I don’t know what her face revealed, what intentions were there to be read, but a black man, she says, who was sitting at a nearby bench just said to her softly, “don’t do it, lady”.

Brooklyn

In the last year my studio space has changed somewhat drastically. Since I moved into my partner’s Brooklyn apartment, my studio space is smaller, sparer, and stranger. In Queens, where I lived alone, my whole apartment was my studio so my portrait work had the run of the place. I had my sittings perch on my wine-colored futon, or lay on the deep brown covers of my bed, or sit on the red, yellow, and orange geometric-patterned rug on the floor. There, in my Queens apartment, I arranged things that were in the room around my sittings. For Michelle, I placed several of my pottery pieces at her feet with a dagger sticking out of one of the pots. For John, I laid a katana across his reclining body. I surrounded Jasmine with books and then ripped pages out of one book we selected together and then I scattered the torn pages around her. I scattered pink and white carnations around and on Caleb that I plucked out of a vase on the windowsill.

Now, here in Brooklyn, a small back room serves as my studio. My portraits in this room are stark compared to the ones done in Queens. My sittings have only room enough to sit on a small, skeletal chair in front of a white, yellowing wall or recline on the unpolished wood floor. I try to dress the portraits up with a plant at a sitting’s feet, or a blue shawl across a shoulder. The portraits are not the same here in Brooklyn. The color is gone. The people who come to sit are wearing white. Like spirits.

Before I moved in, my partner Chris used this small back room for storage. In this room, he stored the clothes of the three dead matriarchs who raised him. He stored his now grown son’s toys and a small bed frame, a bookshelf full of crumbling paperbacks, a dresser full of old bills, a newspaper with a headline reporting the assassination of JFK. It is a room for ghosts and dusty memories. So it is no wonder that my practice has turned to memory and specters.

The process with which I am working with memory is complex and haunting.

Years ago, my mother put together an album for me consisting of family photographs mainly capturing my childhood. The pictures are 33 millimeter photographs stuck behind cellophane pages in a Disney-themed photo album. In my process, I leaf through the cellophane covered pages and select images. The criteria, at first, seemed to be interesting and balanced composition. But I soon realized that was not the criteria with which I was selecting images. My true criteria, I realized, was that there had to be room in the composition for an insertion. Not just physical space in the composition, but room for me to exorcise childhood impressions and illustrate childhood stories by inserting symbols, alterations—ghosts. The chosen photograph had to summon in me a story not being told.

The path to this project is somewhat unclear. It wasn’t something that was suggested and it wasn’t something that I had ever previously conceived of. In fact, I regarded the use of photographs as a reference for painting as something of a cheat at worst and a somewhat meaningless activity at best (why, I thought, recapture a moment in paint that has already been captured in a photograph?). This is why I have always fashioned my portrait work after Lucien Freud and Alice Neel—who both worked solely from live sittings.